How it Works: Vapor Drive

To understand the importance of permeable and impermeable products as they relate to the construction of your home, you need to understand how vapor drive works.

When considering building materials, you hear a lot about their permeance. This issue’s article on spray-foam insulation, “Spray Foam: What Do You Really Know?”, is no exception. To understand the importance of permeable and impermeable products as they relate to the construction of your home, you need to understand vapor drive. Here’s how it works.

Seasonal factors play a part in vapor drive

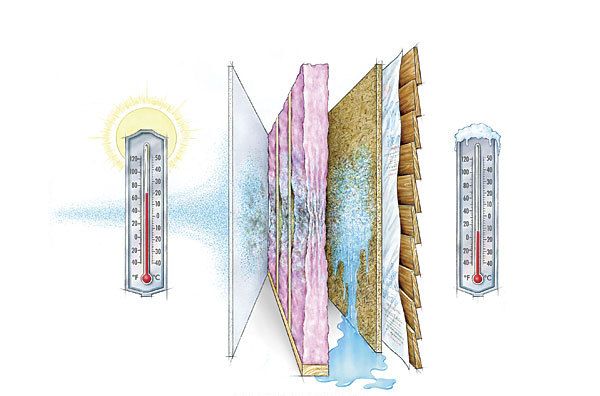

Water vapor constantly diffuses through building materials from the warm, humid side of a house toward the cold, dry side. The cause of this movement is heat and moisture. So in the summer, when a lot of homes are air-conditioned, vapor is driven toward the interior. In the winter, vapor drive is toward the exterior. Vapor drive is the least significant cause of moisture problems in a house, but it’s still really important. When water vapor passes through an assembly and comes in contact with a surface that has a temperature below the dew point (the temperature at which water vapor condenses), then it becomes a wood-rotting, mold-feeding liquid.

There are three ways to reduce condensation within an assembly. By placing a vapor retarder on the warm side of the house, the rate of vapor infiltration is decreased. Using relatively vapor-permeable materials on the cold side of the house helps to allow any vapor in the assembly to dry. Finally, the temperature of building materials can be kept above the dew point by adding a layer of exterior rigid-foam insulation or by filling the cavity with closed-cell spray foam. Closed-cell foam performs well because it’s semi-impermeable, so vapor is always contained to the warm side of the wall.

Climate dictates solutions

Until 2007, the International Residential Code (IRC) treated the country like a single cold climate and offered only one solution to vapor drive. The code required that a vapor retarder be installed on the interior (warm) side of assemblies. However, most of the country has both heating and cooling seasons, so sometimes the cold side is the inside of the wall or roof instead of the outside. The old codes created a risky situation that could cause problems in the summer, especially if the local code official insisted that a vapor retarder meant a polyethylene sheet. When you fill a wall with a highly vapor-permeable insulation (fiberglass batts) and cover one side of it with a virtually nonpermeable vapor retarder (poly), the vapor retarder will be on the wrong side of the assembly for part of the year and inhibit the wall’s ability to dry.

The IRC now breaks the country into eight climate zones and recognizes three classes of vapor retarders that have different levels of permeance (see “What’s the Difference: Vapor Barriers and Vapor Retarders” FHB #202). Generally, the IRC demands that a class-I or -II vapor retarder be installed on the interior side of homes in climate zones 5 and above, and in marine 4. However, if you’re building in a humid climate in zone 4, 5, or 6, and you air-condition your house in the summer, you may be concerned about having a vapor retarder in the “wrong” position for part of the year. If this is the case, just be sure to use a class-II vapor retarder on the interior of the wall. You also can use closed-cell spray foam in the cavity or a layer of exterior rigid foam, with a class-III vapor retarder on the interior.

When building in hot, humid climates (zones 1 to 3), you shouldn’t have a vapor retarder on the interior side of the wall. This allows any water vapor that makes its way into the wall, which can be tempered by closed-cell foam or exterior rigid foam, to dry to the interior.

Drawings by: Don Mannes

Fine Homebuilding Recommended Products

Utility Knife

Caulking Gun

Respirator Mask