Choosing a Deck Foundation

Learn about the various types of deck footings that help spread point loads over a wider area.

Deck foundations are different from house foundations because the load is concentrated at specific points on the ground rather than being spread around the whole perimeter. Even though a deck weighs a lot less than a house, this point loading means that you must give some thought to foundation design.

With the exception of solid rock, no soil type can hold a point load for long without some settling. That’s why all types of foundations have thickened weight-bearing supports—called footings—at their base to help spread point loads over a larger area. Depending on climate conditions, footings may be very close to the surface or may need to be deeply buried 4 ft. or more to get below frost level. If you live in a mild climate, your footings may be on the surface or only need to be buried a little, and you may be able to start your deck-post framing right from the footing itself by buying (or making) a simple one piece block (called a pier block). But if your footings need to be deeper than about 12 in., you’ll need to add a concrete column (called a pier) or a buried post to get to above-ground levels. If you have any doubt about the right foundation for the conditions, consult an engineer.

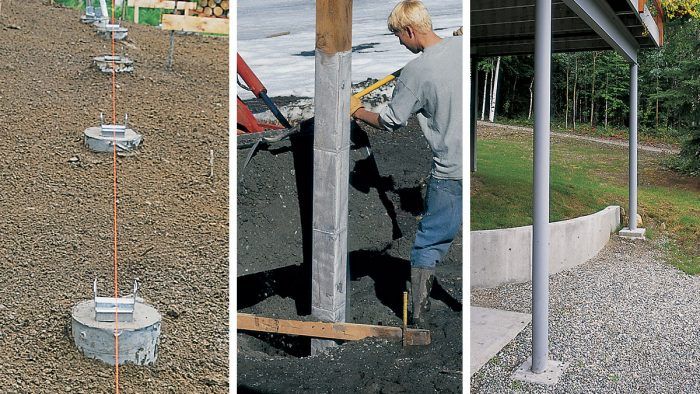

Combination footing-and-pier-foundations

My favorite type of deck foundation is a footing buried below frost level with a concrete pier that brings the foundation up to grade (or finished ground level). In cold climates, the buried footing is required by most building codes because it helps avoid frost heaving (See “How It Works: Frost Heave”). A buried concrete footing is also permanent, and putting it on solid, undisturbed ground makes it less likely to be affected by groundwater and runoff.

According to Code

Building codes vary across the country and may require different types of foundations, depending upon local requirements for frost protection, high winds, earthquakes, and environmental issues. Your local building department will probably request a foundation detail showing foundation type, depth, sizes, and any reinforcements. During the construction process, you should count on at least a couple of visits from the building inspector, who will want to make sure that your deck conforms to code.

For most of my decks, I pour the footing and pier at the same time with an internal piece of rebar. This kind of one-piece foundation that is wider at the bottom helps spread the point load and act as an anchor against frost jacking, another cold climate concern. With large or complicated footings, it is sometimes easier to pour the footing first and the pier separately. Casting an L-shaped piece of rebar in the footing in the first pour and leaving the vertical part sticking up to catch the pier in the second pour will provide the same anchoring effect.

Pier-block foundations

In certain situations, a combination footing/small pier—called a precast pier block—offers a simple foundation solution. These pyramidal shaped blocks can be bought at most building supply stores and are usually cast with some type of bracket on the top for attaching a wood post. These piers should be used only on stable soil and in warmer climates with a shallow frost line, but there are ways to improve your success in less than perfect conditions. For example, it is always a good idea to dig down about 6 in. to 12 in. deeper than the pier block to get to solid ground. Then refill the hole with compacted gravel to aid drainage, set the pier so a few inches are above grade, continue filling around the pier with gravel, and finish with a layer of dirt. Partially burying the pier will add to its stability and help make it less noticeable.

In Detail

If you live in an area where seismic activity or frost isn’t a problem, precast pier blocks are quite handy. Some have two open, perpendicular grooves cast into the top, sized to allow a 1 1/2-in. wide board to slide in on edge. These grooves don’t do much to keep the wood anchored to the block and are used only on ground-level decks, but the blocks are easy to work with in circumstances that don’t require a buried footing. I’ve also seen pier blocks with wood blocks cast into them, but avoid these. The wood blocks (usually untreated) will rot quickly in contact with the concrete. They’ll also split when a post is toenailed to them and don’t provide a secure connection to the deck.

Keep in mind that the bases of these pier blocks are usually not very big and so might settle unevenly in weak soils. If your calculations call for a larger footprint than the pier block provides, it helps to dig a little deeper, add the layer of gravel, and then pour a larger footing for the pier block to sit on. While pier blocks have their limitations, they can provide a good, easy foundation if frost depth isn’t deep and drainage is good. If soils are dry, I often use pier blocks for small details like the bottom of stairs, even in my cold Alaskan climate.

Continuous-post foundations

Sometimes a single pressure-treated or decay-resistant wood post may be used to get from a buried footing up to grade and then continue on to the deck framing. This system would be a good choice in areas with a lot of seismic activity that need the additional lateral stability gained by eliminating the connection from foundation to post at grade level. The post can simply sit on the footing if the post is buried several feet to resist lifting forces. Sometimes the base of the post, spiked with stainless-steel nails, is cast into a thickened footing to prevent uplift. In both cases, it is essential to backfill with gravel around the post when damp, freezing soils are present to ensure good drainage and help resist frost jacking. Finishing the backfilling with several inches of regular dirt helps seal the hole against water intrusion.

While the continuous-post foundation can be easier to build and may be necessary for lateral stability, it does have one big disadvantage. Below-grade inspection of the wood and any subsequent repairs needed will require removing the entire post down to the footing. Although modern treated lumber is of good quality, I am suspicious of larger timbers that “check” or crack open as they dry and expose poorly treated interior sections to moisture, rot, and bugs. An alternative is to use steel posts, which are stronger, can be made rust-resistant, and are comparably priced. Steel posts will need a bracket at the top to allow attaching wood beams but these are easily added by your steel supplier.

RELATED STORIES

A Solid Deck Begins with Concrete Piers

It’s Time to Consider Helical Pile Footings

Fine Homebuilding Recommended Products

Drill Driver/Impact Driver

N95 Respirator

Metal Connector Nailer